Blasting History into the Present |

|---|

| Home | Context | History | Practice | About |

|---|

| re-enactment | preselis | ford | dolwilym | harvest | dancing | |

|---|

|

|---|

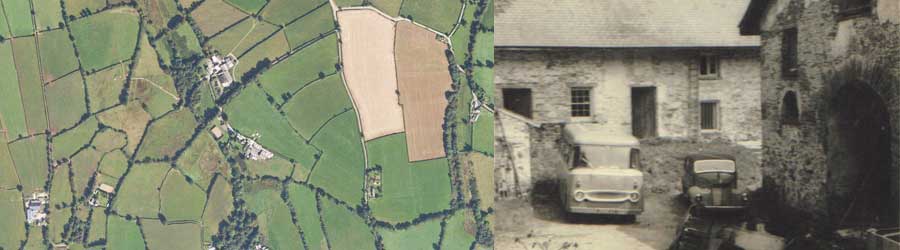

DOLWILYM: Renovation and the changing landscape. ‘Dolwilym was the centre of the universe ... every saturday night there was a gig ... there was always something going on.' This particular history is a complex one, and in terms of the sensitivities (or their lack) of land appropriation and property-buying, which became synonymous with the forces of cultural, and economic, dominance in Wales, we must be reminded that this was pre-1980s, pre-Thatcher, pre-flexible mortgages (although mortgages were becoming increasingly available in the 1970s), and pre-arson attacks on second homes. Are we in a naïve space/time? Dolwilym, a mansion with house and barns, near Glandwr, on the landward-facing side of the Preseli Hills, in North Pembrokeshire, provided a magnificent hub of activity. In this essay, Dolwilym provides a conduit into thoughts about the reinvention of working Welsh cottages and subsequent changes effected on the landscape. Most of these cottages were being deserted by farmers in favour of newly-built, warmer, larger-windowed, lower maintenance bungalows and houses. So the completely ruined, or semi-ruined, cottages were willingly handed over to be reactivated. New drainage was dug to stop ground floors from flooding, rooves were fixed, windows repaired, gardens tidied and planted, kitchens made usable and parties were had. I want to frame thoughts about the reinvention of the Welsh cottage within what ethnographer George Marcus calls the 'salvage mode' and the 'redemptive mode'. The former identifies a place 'before the deluge', so a culture 'on the verge of transformation' is salvaged. In relation to this, the 'redemptive mode' recognizes a 'golden age', which represents authentic cultural life (both modes are idealistic). A 'golden age' might be seen as pre-modern or pre-capitalist and, especially, would be physically, or geographically, removed, and so involve journeying 'up-river' or to a 'back country' where 'they still do it'. I want to contrast such a view, and its relationship with the commodification of such property, with the daily habits and practices of those who lived, and still live (in many cases), in them. This is, then, a history which attempts to pit oppression (represented by the ideology of consumption) against liberation (a utopia of plenty). A Welsh cottage in the 1970s contains the past, present and future - materially and environmentally. This is, after all, in so many ways, an environmental history - that is, a history which confirms actions, networks and habits being highly influenced by, and in a relationship with, the environment. The traditional cottages contain, via their heavy stonework and low profile, the character of working the land, living on the land, ‘hewn from nature’. But they slip between function and form or, over time, between Marx’s use and exchange value, where the value of an object is no longer determined by what it is useful for, but by its relation to money, to other objects, and dreams. ‘It was much easier for us because property was so cheap’ (whether buying, renting, squatting…). But, given the appropriation of property, it was also thought that a feudal/tribal analogy could be drawn. Where England was feudal, displaying not only a tight grip on property and the way property should be used, Wales was tribal because property could be played with without the authorities coming down on you. ‘Although there was a certain amount of antagonism, that was where the hippies fitted in with the Welsh – they were both tribal.’ This sentiment is echoed by Emyr Humphreys (in The Celtic League Annual, 1971), who attaches 'the psychology of the Welshman' to a 'tribal lay' which is rooted in 'the living past, the history and tradition'. Can this distinction, and separation from England, also be applied to an urban/rural discourse? And how, in this case, did the rural become a place to reconfigure utopian ideals by reattaching them to history. That Dolwilym itself carries all the symbolism and practicalities of antique and antiques is a part of its significance. This is a place containing relics ready to be rediscovered. Its fading grandeur supported the feeling of a rich new life residing in the past. ‘Aesthetically it was beautiful, but practically, very hard.’ (Can it be contrasted with John Seymour’s farm in the way it drew people, keen to re-energize a past?) So while ‘there were all these households, or little groups, living off the main road, down tracks…’ Dolwilym provided the feeling of ‘being an aristocrat – very poor, but like an aristocrat because there was so much time to socialise.’ So ‘The Shed’ became a venue for gigs and plays, the gardens a place for Maypole dancing and seasonal celebration, and other buildings used as habitats with basic ame nities. A new kind of Arcadia. |

Click on images, below, to hear soundclips from interviews, 2012.

|

|

||