Blasting History into the Present |

|---|

| Home | Context | History | Practice | About |

|---|

| re-enactment | preselis | ford | dolwilym | harvest | dancing | |

|---|

|

|---|

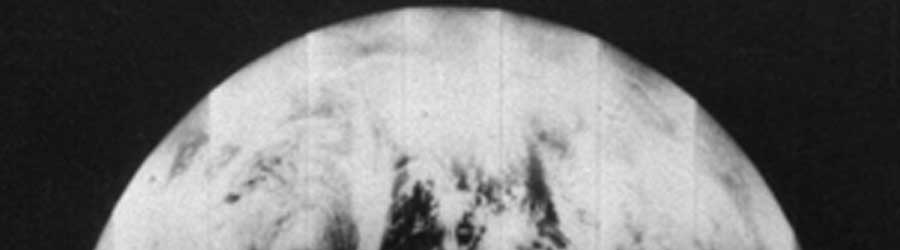

HARVEST: Going back to look forward – back to the land, back to nature. No running water and no electricity was a novelty for many, and supported by youthful enthusiasm. ‘We couldn’t get anything to work – everything leaked, nothing grew, the goat died, and so did the donkey…’ When searching for literature concerning back-to-the-land, or self-sufficiency in the 1970s, roads generally lead to California, where the bright sunshine, good soils, and plentiful lands provided an ideal climate for such self-sufficient ideologies to bear fruit, and indeed they still do. Of course it's different in Wales: 'I've become waterproof' said one, and you had to be, in all sorts of ways if labour and leisure were to be embraced out of doors. Wales was already home to ideas of self-sufficiency and back-to-the-land-ism. Plaid Cymru, when it was first formed in 1925, had already been working through ideas of the rural, trying to build a Welsh identity on notions of wholesome rural spirituality, but while holding onto the almost opposite ideas of progress and modernity - a difficult path to tread. There is a paradox, because in the context of Wales, such back-to-the-land, counter-cultural practices are often represented by a cultural hegemony (i.e. English in Wales). But we must remember that even within this particular slice of history there is enormous complexity, so within the broader brushstrokes of urban-to-rural, England-to-Wales, there are those who, fitting into neither categories, nonetheless had shared aims. Indeed, confusion and cultural conflict is evident in those who grew up in Wales and found a home for their counter-cultural critique residing in something that appeared to be brought from England. This came not just in the form of hippy culture – ‘heads’ – but in the form of publications such as the feminist, anti-capitalist magazine Spare Rib. A book written in 1971, aimed at English speakers in order to assist an understanding of Welsh activism, called The Welsh Extremist by Ned Thomas, begins by noting alliances with the English New Left, which sought to critique institutional structures. Wales' fight for its language, asserts Thomas, is synonymous with a fight against 'the destructive march of late capitalism, which broke human communities not for the sake of some better society based on the cities but so that the wheels of production shall spin faster.' Thomas is keen to evoke parallels across Europe, from Hungarian 'extremists' in Budapest to Parisian students and, of course, the Irish. Everyone feels that this drive for productivity is spinning out of control, and is essentially flawed. In this case, it is the landscape as productive force which is striking - it is there to re-nourish an over-urbanised, overly consumer-focused culture. The first images of the earth from space, such as the one pictured above, which I believe was actually the first to be taken from the moon, on August 23rd, 1966, became part of a radical view of the world, prompting a new ecological awareness, which became, for many aligned with anti-capitalism. 1972 saw the publication of Gordon Rattray Taylor's The Doomsday Book which outlined the fragile state of the planet, hurtling through space with limited resources; and the BBC’s television series Survivors (1975-77) gave us characters dealing with a post-apocalyptic scenario. Edward Goldsmith and Robert Allan’s A Blueprint for Survival (1972) outlined a need to reduce the size of our communities in order to advance a deep ecological wellbeing, and this was interpreted by many as a need to move to the countryside, or back to the land. So, the practical ideas already being developed by broadcaster and writer, John Seymour, gained more attention. Having written The Fat of the Land in 1961, which gave a frank account of setting up a smallholding in Suffok, he moved to North Pembrokeshire, continuing to write about working the land as environmentalist and standing against consumerism and modern industrialisation. In 1976, Seymour published his Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency, which became a practical guidebook to complement such books as A Blueprint for Survival, and is still widely used today. And, of course, there was The Good Life (1975-78), which tried to make light of the situation while also attempting to sustain its image as marginalised. Seymour also drew attention to the countryside which, in the 1970s, was suffering just as much as the cities under the weight of industrialization, mechanization, and the mantra of ‘economic growth’. A cow produced 200 gallons more milk than in the 1950s, a hen laid twice as many eggs; and an estimated £1.5 billion in subsidies went towards replacing people with fleets of combine harvesters, tractors and land rovers. It was seen in Wales that there was a sharp decline in species of flora and fauna around 1975 in particular, which is being attributed to huge increases in the use of chemicals to aid farm productivity – a process that had begun post-WWII. The landscape was being irrevocably altered in just the same way as urban planners were changing the cities. And, as mentioned, Wales already had a history of wrestling with its own identity in relation to the rural.(Gruffudd 1994) A writer from the NME, in August 1975, wrote: 'You see, keep it quiet but Wales and the West Country have become occupied territory. The hardcore freak communes and the lightly-crazed cottage dwellers who all declare, with suitable fragility, "Cities just got too heavy", are digging in deeper and deeper. And once having evacuated any last remnants of their sanity to safety in the myth-drenched furthest backwoods, it isn't then solely down to catatonic laid-backness.' It is a myopic view ('occupied'? - don't people already live there?), but one which demonstrates the disenchantment with urban life. Today, the question is more conscious of the relationship between urban and rural space, and of the people involved, including pensioners in search of a rural idyll, young adults seeking work in the cities, rural policies, EU policies, and so on, asking: how can rural space be both productive enough to keep the towns and cities alive, but also ‘picturesque’ enough to provide spiritual nourishment for urban populations? But these are questions for capital. We also need to be aware of the 'occupied territory' by which I mean the spaces of resistance that form in relation to, and to challenge, any sense of overpowering hegemony.

|

Click on images, below, to hear soundclips from interviews, 2012.

|

|

||