Blasting History into the Present |

|---|

| Home | Context | History | Practice | About |

|---|

| re-enactment | preselis | ford | dolwilym | harvest | dancing | |

|---|

|

|---|

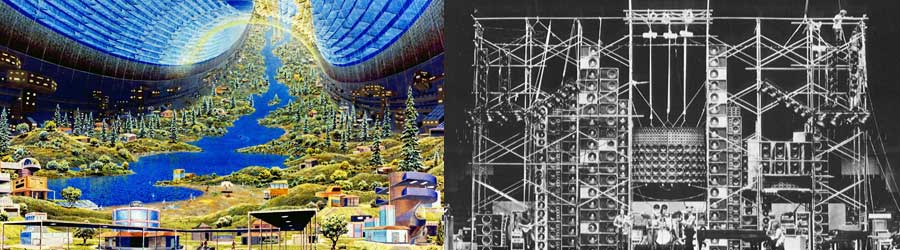

RE-ENACTING: Historical returns, going back to look forward. ‘Just when people seem engaged in revolutionising themselves and objects, in creating something that has never existed before - precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis, they anxiously conjure up to their service the spirits of the past.’ The above quote, by Karl Marx, was observed in relation to the French revolutionaries who turned, for inspiration, to the Roman republic, copying its models of citizenship and liberty. Here, it is about a ‘back to the land’, or ‘back to nature’ ideology, an ideology that has been summoned regularly throughout history, and used to renegotiate a relationship with nature. And the crises that provoke such returns are often associated with a rejection of the urban, where urban centres are seen to embody ecological disconnection and self-indulgent consumerism. The rural drew people away from urban pollution: ‘we’d been living in some heavy-duty urban environments..’ said one. The focus, here, is a history of counter-cultural migration, and practice, in North Pembrokeshire, in the 1970s. Individuals and communities moved – often from urban to rural spaces - in order to fulfil their dreams, and experiment with going back to ‘nature’. These experiments gave rise to new, or revised, social and economic structures, such as small-scale farming, the production of artisan foods, the establishment of ancient heritage sites, alternative schools, and a revival of craft skills. It looked forward with revolutionary intent, while drawing on deeply ‘traditional’ values. To frame this historical returning, two references are important. The first relates to Walter Benjamin, Marxist philosopher, and critic, who was writing in Europe until 1940, and developed a complex way of looking at how the past exists in, and for, the present. His Marxist, materialist approach to history was combined with a fascination with ideas of the mystical and redemption, and the power they exerted over our dreams and desires (something Marx put down to ‘the spell of capitalism’). Working in Europe during the rise of fascism, Benjamin wanted to press history in order to retrieve its revolutionary spirit. He wrote that ‘In every era the attempt must be made anew to wrest tradition away from a conformism that is about to overpower it.’ In other words history and, therefore, the way experience is remembered, is written and controlled by dominant powers. Therefore investigating, and re-presenting, marginal practices from the past is another way of questioning mainstream ideologies past and present. The historian, sociologist, philosopher, or polymath, Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was so sceptical of the way history was written that he refrained even from using the word ‘history’. Instead, he preferred terms such as ‘genealogy’ or ‘archaeology’ to demonstrate temporal processes, continuity and multiple interpretations. For Benjamin, searching history’s myths, technologies and forms of social organisation, his kaleidoscope of images included historical details, literary accounts, philosophical reflections and cultural critiques. His approach to history, then, was not conventional, but in this way he attempted to rescue the ‘rags and refuse’ of history – the missing details - in order to seek out the ‘shocks’ and ‘flashes’ of utopian thinking: our ‘wish images’ which, often, might be contained within objects, artefacts and images, or even remembered experiences. To reconcile oneself with the present, in order to revolutionize it, one needed, in Benjamin’s thinking, to reconcile oneself with the past. The second reference moves such thinking into practice. In 2001, the Battle of Orgreave, that bitter clash between striking miners and the newly-equipped riot police of 1984, was re-enacted. Much in the style of conventional battle re-enactments, the event took place on the original site of Orgreave village, next to the coking plant, and played with what is essentially a mainstream cultural obsession, which has seen historical re-enactments taking place in Roman times to celebrate victorious battles, to re-living the American Civil War (and even re-enacting a different outcome), the Second World War, War of the Roses, Medieval battles, and so on. It was undertaken by the artist Jeremy Deller, in collaboration with Channel 4 and the commissioning agency Artangel, and was a re-enactment which allowed for a rethinking of history. It was a cathartic process for participants (many of whom were part of the original battle), allowing for reflection on specific details, as well as the wider political picture. For one observer, thinking about the union movement, pride in work, solidarity and community strength, the event called for a re-energising, asking ‘where are we now?’, ‘what’s possible now?’, ‘do we still have the capacity?’ As much as the event itself, it is the process of recovery that resonates. Gathered from media coverage, political accounts, and personal memories, and colliding ‘high’ culture (Deller won the Turner prize in 2004) with popular culture, the process of reconstructing Orgreave was wide open to multiple interpretations: what was included? What was left out? Here then, is a history of attempts, how such attempts are relevant, and how such ever-present, ever-suppressed, utopian desires might be found embedded in myths (stories), places, objects and technologies as allegories for our future. Returning to Walter Benjamin, who noted, in his work on the function of allegory, that ‘Any person, any object, any relationship can mean absolutely anything else’, nature, he observed, is especially abundant with the allegories it provides for our own sense of meaning (indeed, is this the only purpose nature can serve?). What follows is an ethnographic reconstruction via descriptions and comments, events and objects, which suggests connections, past and present, between personal and collective dreams and experiences.

|

Click on images, below, to hear soundclips from interviews, 2012.

|

|

||